Monday, January 31, 2011

Saturday, January 29, 2011

Wednesday, January 26, 2011

Monday, January 24, 2011

Saturday, January 22, 2011

Dark Roasted Weirdsville

Check it out: a brand new Dark Roasted Blend piece I did just went up: this time about artists who work with the earth itself.

Go to a museum and look at the paintings, or the sculpture. Go to a bookstore and read the novels, or the stories, or the poems. Go to a concert and listen to the music.

Look out the window ... and see art? Some artists use oils, charcoal, watercolors, words, or notes but others use the earth itself, sometimes on a scale that, to appreciate it, means stepping far away from it: very far away.

Travel to Catron County, New Mexico, for instance and you'll see a work that is immediately, and quite literally, striking. Created by Walter De Maria, The Lightning Field is 400 steel poles set in a grid covering one mile by one kilometer portion of desert land. The Lightning Field is impressive, a haunting visa of steel spears against the dramatic landscape of the Southwest, but what gives it that literal striking beauty is that De Maria plan for his work involves those poles interacting with one of the most beautiful signs in the desert: lightning. Given the right set of circumstances, nature itself paints itself in brilliant illuminations of forked electricity, shaped and sculpted by De Maria's metal rods.

Not that far away, in Rozel Point, Utah, you'll see an installation that, because of the on-again, off-again nature of the material it's made of actually vanished for close than 30 years. Created by Robert Smithson using natural rock, Spiral Jetty is exactly that: a coiling formation of stone that, when it was first created in 1970, was harshly black but as it aged its become more and more pink and white because of the its home in the Great Salt Lake. As with The Lightning Field, Spiral Jetty works with the earth itself, not just in appearance, meaning color, but also as in appearing and disappearing: when the water rose in the lake the work it did it's already-mentioned disappearing act, only to reappear again recently.

While not as large in scale as Smithson or De Maria, there's an artist whose work has been known to bring tears to even the most jaded of eyes. Andy Goldsworthy works with nature, and nothing else, to create some truly unique, and absolutely beautiful, art.

No glue, no supports, no paint ... nothing but grass, stone, ice, and the earth: Goldsworthy creates wonders with just the at hand wonder of the natural world.

Still existing on the earth, the art of Jim Denevan, is so large, so staggering, that to appreciate them you have to step away from it all: from the ground and even, in some cases, the earth itself. Created, like Goldsworthy, with nature itself, one of Denevan's creations is acknowledged as the largest artwork created. Ever.

At over nine miles across, this Denevan's creation in the Black Rock Desert of Nevada, is the one for the record books ... that is, until Denevan or another artist likes him, goes for something even larger:

Another earth artist is Michael Heizer's work-in-progress called City, in Nevada. Almost as big as it's namesake at one and a quarter miles long, Heizer's creation, however, is not steel and cement but stone and other natural materials.

James Turrell, too, uses the earth itself for his work but unlike some other environmental artists he uses not just the ground but also the sky above. His Roden Crater, which is considered on the list of immense artworks with Denevan's creations, is an ongoing work that will, eventually, transform a natural crater in Flagstaff, Arizona, into an open air observatory where the earth will provide a naturally framed view of the sky above.

But if we have to talk about the earth and art, as well as art so big it can only be appreciated by being far above it, we have to travel to Peru, and back several thousand years into the past.

A favorite of ancient astronaut believers, the fact is that the Nazca lines were created by men and women who may have been working with simple tools but utilizing their very intelligent minds. Created by removing the native gravel to expose the different-colored ground under, the lines depict a wide variety of shapes and forms, some purely geometric, but others representing the animals the Nazca natives were most familiar with: spiders, fish, llamas, lizards, hummingbirds and others.

While the execution is phenomenal, a low whistle is absolutely needed when that level of skill of coupled with the size of the lines. The largest of the forms stretches almost across 900 feet across and pretty much all of them are all but invisible ... unless you happen to be high above the earth they were carved into.

Jack Clifton, author of The Eye of the Artist, said, "Man's reaction to his earth expressed by means of a medium is art." In the case of these wonderful artists, the ground beneath our feet and the sky above our heads their art is the earth itself, a celebration of the world literally all around us.

Go to a museum and look at the paintings, or the sculpture. Go to a bookstore and read the novels, or the stories, or the poems. Go to a concert and listen to the music.

Look out the window ... and see art? Some artists use oils, charcoal, watercolors, words, or notes but others use the earth itself, sometimes on a scale that, to appreciate it, means stepping far away from it: very far away.

Travel to Catron County, New Mexico, for instance and you'll see a work that is immediately, and quite literally, striking. Created by Walter De Maria, The Lightning Field is 400 steel poles set in a grid covering one mile by one kilometer portion of desert land. The Lightning Field is impressive, a haunting visa of steel spears against the dramatic landscape of the Southwest, but what gives it that literal striking beauty is that De Maria plan for his work involves those poles interacting with one of the most beautiful signs in the desert: lightning. Given the right set of circumstances, nature itself paints itself in brilliant illuminations of forked electricity, shaped and sculpted by De Maria's metal rods.

Not that far away, in Rozel Point, Utah, you'll see an installation that, because of the on-again, off-again nature of the material it's made of actually vanished for close than 30 years. Created by Robert Smithson using natural rock, Spiral Jetty is exactly that: a coiling formation of stone that, when it was first created in 1970, was harshly black but as it aged its become more and more pink and white because of the its home in the Great Salt Lake. As with The Lightning Field, Spiral Jetty works with the earth itself, not just in appearance, meaning color, but also as in appearing and disappearing: when the water rose in the lake the work it did it's already-mentioned disappearing act, only to reappear again recently.

While not as large in scale as Smithson or De Maria, there's an artist whose work has been known to bring tears to even the most jaded of eyes. Andy Goldsworthy works with nature, and nothing else, to create some truly unique, and absolutely beautiful, art.

No glue, no supports, no paint ... nothing but grass, stone, ice, and the earth: Goldsworthy creates wonders with just the at hand wonder of the natural world.

Still existing on the earth, the art of Jim Denevan, is so large, so staggering, that to appreciate them you have to step away from it all: from the ground and even, in some cases, the earth itself. Created, like Goldsworthy, with nature itself, one of Denevan's creations is acknowledged as the largest artwork created. Ever.

At over nine miles across, this Denevan's creation in the Black Rock Desert of Nevada, is the one for the record books ... that is, until Denevan or another artist likes him, goes for something even larger:

Another earth artist is Michael Heizer's work-in-progress called City, in Nevada. Almost as big as it's namesake at one and a quarter miles long, Heizer's creation, however, is not steel and cement but stone and other natural materials.

James Turrell, too, uses the earth itself for his work but unlike some other environmental artists he uses not just the ground but also the sky above. His Roden Crater, which is considered on the list of immense artworks with Denevan's creations, is an ongoing work that will, eventually, transform a natural crater in Flagstaff, Arizona, into an open air observatory where the earth will provide a naturally framed view of the sky above.

But if we have to talk about the earth and art, as well as art so big it can only be appreciated by being far above it, we have to travel to Peru, and back several thousand years into the past.

A favorite of ancient astronaut believers, the fact is that the Nazca lines were created by men and women who may have been working with simple tools but utilizing their very intelligent minds. Created by removing the native gravel to expose the different-colored ground under, the lines depict a wide variety of shapes and forms, some purely geometric, but others representing the animals the Nazca natives were most familiar with: spiders, fish, llamas, lizards, hummingbirds and others.

While the execution is phenomenal, a low whistle is absolutely needed when that level of skill of coupled with the size of the lines. The largest of the forms stretches almost across 900 feet across and pretty much all of them are all but invisible ... unless you happen to be high above the earth they were carved into.

Jack Clifton, author of The Eye of the Artist, said, "Man's reaction to his earth expressed by means of a medium is art." In the case of these wonderful artists, the ground beneath our feet and the sky above our heads their art is the earth itself, a celebration of the world literally all around us.

Friday, January 21, 2011

Weirdsville On The Cud

Here's another special piece I did for the great folks at the Aussie site The Cud. This time it's about the theft of a very famous work of art.

If it had been done in this age of iphones, ipads, and the rest of our high tech ilives, the movie would have had Clooney or Willis dangling upside down over a pick-up-sticks weave of alarm lasers while a geeky cohort (maybe Steve Buscemi or Alan Cumming), face green from the digital overload bouncing up from a laptop, rattles off a second-by-second update on the imminent wee-oo-wee-oo arrival of the stern-jawed Groupe d'Intervention de la Gendarmerie Nationale.

But while the lady did vanish – a very, very special lady – the means of her vanishing, while maybe a tad less dramatic, is no less fascinating. While you'll no doubt immediately recognize the lady in question, you may not know her full name, or some of the more interesting details of her portrait. Begun by a certain well-known artist back in 1503, the likeness of Lisa del Giocondo wasn't finished until some years later, around 1519. After the death of this rather well known artist, the painting was purchased by King François I, and then, after a certain amount of time and other kings, it finally ended up in the Louvre. An interesting note, by the way, is that – while not a King – the painting was borrowed from the Louvre by Napoleon to hang in his private quarters, and was returned to that famous French museum when the Emperor became ... well, not the Emperor.

Its official title is Portrait of Lisa Gherardini, wife of Francesco del Giocondo but the smile says it all, and in 1911 it was stolen – and wasn't returned until 1913.

While much of the theft is still a mystery, what is known is that on August 22, 1912, Louis Béroud, a painter and fan of the legendary Mona Lisa, came into the Louvre early one morning to study the famous work of Leonardo da Vinci, instead finding a bare wall. In a pure Inspector Clouseau bit of history, the museum staff didn't immediately put bare wall and missing painting together and instead thought the painting had been taken to be photographed. It took Béroud, checking with the photographers themselves, to bring it to the attention of the guards that the painting had been stolen.

Suspects were many and varied: a curious one was Guillaume Apollinaire, the critic and surrealist, who, because he can once called for the Louvre to be burnt to the ground, was actually arrested. While no-doubt annoying, he was eventually cleared and released, but not before trying to finger, unsuccessfully, a friend of his for the theft, another rather well known painter by the name of Pablo Picasso.

Alas, the actual thief and the method of the robbery are almost painfully plain, though the man and the means weren't discovered until much later. In 1913, Vincenzo Peruggia, a Louvre employee, was nabbed when he contacted Alfredo Geri, who ran a gallery in Florence, Italy, about the stolen painting.

The story that emerged after his arrest was that on August 20th, 1912, had Peruggia hid in the museum overnight. On the morning of Sunday, the 21st, he emerged from hiding, put on one of the smocks used by employees and, with ridiculous ease, simply took what is arguably the most famous painting in the world and put it under his coat and walked out the door with it. When the gendarmes later knocked on Peruggia's door they'd simply accepted his excuse that he'd been working somewhere else the day of the theft, while the painting was hidden under his bed.

What isn't plain, though, was Peruggia's motivation for the theft. While he constantly argued he'd stolen the Mona Lisa for patriotic reasons, to hopefully return it to his native Italy, many believe a more intriguing, more nefarious, more devilishly elegant explanation – an explanation that involves one of the most legendary crooks and conmen who have ever lived: Eduardo de Valfierno.

Born in Argentina, Valfierno, who liked to call himself a Marqués, was a man with not just a plan, but a remarkably clever plan. According to those to believe he had a hand in the affair, the Marqués began by commissioning not one, not two, not three but instead six copies of the painting from the equally-legendary forger Yves Chaudron. Now there's no way anyone would buy a Mona Lisa when the real one was clearly hanging on a wall in the Louvre, so Valfierno hired the poor Peruggia to make off with the original.

Once the original painting was reported missing, Valfierno took his six perfect forgeries and sold them to illicit collectors all over Europe, convincing each and every one that the Mona Lisa they were purchasing was the one and only. Waiting for the elegance? Well, even if Valfierno had been caught, the only thing be could have been nailed for was selling forgeries, which none of the collectors he'd sold to were ever willing to report as it would have incriminated themselves as well. What was an extra bonus, Valfierno could have sold as many copies as he'd wanted as long as the original painting stayed missing.

For those who like to tie Valfierno to the crime, Peruggia only tripped up the whole scheme when he realized that Valfierno had stuck him with the serious end of the crime – the theft – and he'd stumbled when trying to sell the Mona Lisa or, as he claimed, simply trying to return it to his native Italy.

The tale, though, does has a somewhat happy ending: Peruggia, despite the outrage over the theft of the painting in France, was given a rather lenient sentence by the Italian authorities, who felt moved by Peruggia's claim to have been motivated by patriotism. While little is known about the possible mastermind, Valfierno, considering the brains and creativity involved it's not a huge stretch to imagine him doing quite well afterward.

Meanwhile, The Portrait of Lisa Gherardini, wife of Francesco del Giocondo, was returned to her noble spot in the Louvre where she smiles out as us to this day: her cryptic expression as mysterious as the shadowy history surrounding her theft in 1911.

But while the lady did vanish – a very, very special lady – the means of her vanishing, while maybe a tad less dramatic, is no less fascinating. While you'll no doubt immediately recognize the lady in question, you may not know her full name, or some of the more interesting details of her portrait. Begun by a certain well-known artist back in 1503, the likeness of Lisa del Giocondo wasn't finished until some years later, around 1519. After the death of this rather well known artist, the painting was purchased by King François I, and then, after a certain amount of time and other kings, it finally ended up in the Louvre. An interesting note, by the way, is that – while not a King – the painting was borrowed from the Louvre by Napoleon to hang in his private quarters, and was returned to that famous French museum when the Emperor became ... well, not the Emperor.

Its official title is Portrait of Lisa Gherardini, wife of Francesco del Giocondo but the smile says it all, and in 1911 it was stolen – and wasn't returned until 1913.

While much of the theft is still a mystery, what is known is that on August 22, 1912, Louis Béroud, a painter and fan of the legendary Mona Lisa, came into the Louvre early one morning to study the famous work of Leonardo da Vinci, instead finding a bare wall. In a pure Inspector Clouseau bit of history, the museum staff didn't immediately put bare wall and missing painting together and instead thought the painting had been taken to be photographed. It took Béroud, checking with the photographers themselves, to bring it to the attention of the guards that the painting had been stolen.

Suspects were many and varied: a curious one was Guillaume Apollinaire, the critic and surrealist, who, because he can once called for the Louvre to be burnt to the ground, was actually arrested. While no-doubt annoying, he was eventually cleared and released, but not before trying to finger, unsuccessfully, a friend of his for the theft, another rather well known painter by the name of Pablo Picasso.

Alas, the actual thief and the method of the robbery are almost painfully plain, though the man and the means weren't discovered until much later. In 1913, Vincenzo Peruggia, a Louvre employee, was nabbed when he contacted Alfredo Geri, who ran a gallery in Florence, Italy, about the stolen painting.

The story that emerged after his arrest was that on August 20th, 1912, had Peruggia hid in the museum overnight. On the morning of Sunday, the 21st, he emerged from hiding, put on one of the smocks used by employees and, with ridiculous ease, simply took what is arguably the most famous painting in the world and put it under his coat and walked out the door with it. When the gendarmes later knocked on Peruggia's door they'd simply accepted his excuse that he'd been working somewhere else the day of the theft, while the painting was hidden under his bed.

What isn't plain, though, was Peruggia's motivation for the theft. While he constantly argued he'd stolen the Mona Lisa for patriotic reasons, to hopefully return it to his native Italy, many believe a more intriguing, more nefarious, more devilishly elegant explanation – an explanation that involves one of the most legendary crooks and conmen who have ever lived: Eduardo de Valfierno.

Born in Argentina, Valfierno, who liked to call himself a Marqués, was a man with not just a plan, but a remarkably clever plan. According to those to believe he had a hand in the affair, the Marqués began by commissioning not one, not two, not three but instead six copies of the painting from the equally-legendary forger Yves Chaudron. Now there's no way anyone would buy a Mona Lisa when the real one was clearly hanging on a wall in the Louvre, so Valfierno hired the poor Peruggia to make off with the original.

Once the original painting was reported missing, Valfierno took his six perfect forgeries and sold them to illicit collectors all over Europe, convincing each and every one that the Mona Lisa they were purchasing was the one and only. Waiting for the elegance? Well, even if Valfierno had been caught, the only thing be could have been nailed for was selling forgeries, which none of the collectors he'd sold to were ever willing to report as it would have incriminated themselves as well. What was an extra bonus, Valfierno could have sold as many copies as he'd wanted as long as the original painting stayed missing.

For those who like to tie Valfierno to the crime, Peruggia only tripped up the whole scheme when he realized that Valfierno had stuck him with the serious end of the crime – the theft – and he'd stumbled when trying to sell the Mona Lisa or, as he claimed, simply trying to return it to his native Italy.

The tale, though, does has a somewhat happy ending: Peruggia, despite the outrage over the theft of the painting in France, was given a rather lenient sentence by the Italian authorities, who felt moved by Peruggia's claim to have been motivated by patriotism. While little is known about the possible mastermind, Valfierno, considering the brains and creativity involved it's not a huge stretch to imagine him doing quite well afterward.

Meanwhile, The Portrait of Lisa Gherardini, wife of Francesco del Giocondo, was returned to her noble spot in the Louvre where she smiles out as us to this day: her cryptic expression as mysterious as the shadowy history surrounding her theft in 1911.

Thursday, January 20, 2011

Wednesday, January 19, 2011

Tuesday, January 18, 2011

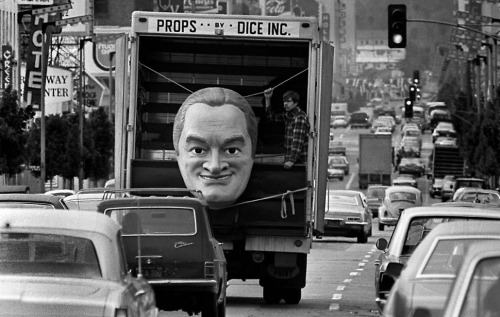

On The Road With Bob

Jan. 28, 1972: A bust of Bob Hope is transported through Hollywood for retouching at a paint shop

Monday, January 17, 2011

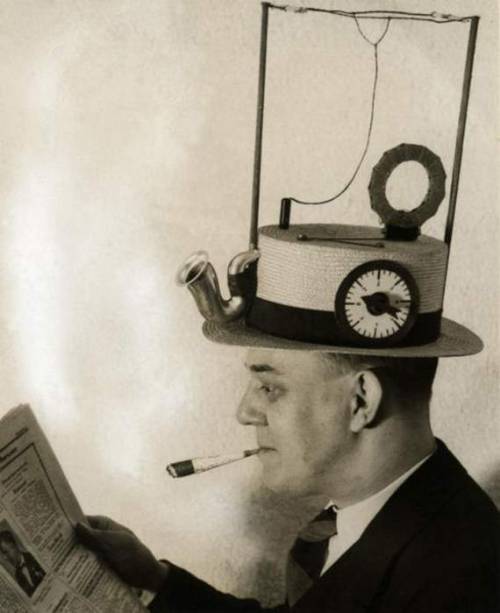

Dark Roasted Biscotti

Here's yet another of my takes on doing a Biscotti for the always-wonderful Dark Roasted Blend. I have to say these are a real kick and a treat to put together!

Friday, January 14, 2011

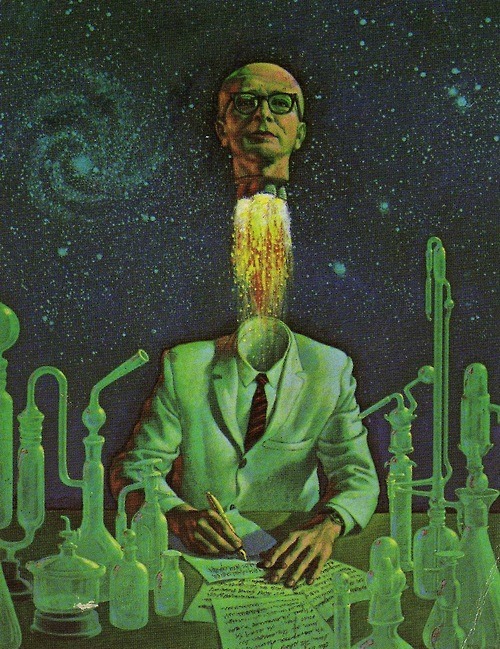

The Bachelor Machine On Smashwords

If you'd like a neat little taste of my erotic science fiction collection, The Bachelor Machine (and why wouldn't you?) check out Smashwords for a peak inside.

Wednesday, January 12, 2011

Tuesday, January 11, 2011

Monday, January 10, 2011

Sunday, January 9, 2011

Movies You Haven't Seen But Should: A Cold Night's Death

Wiki:

A Cold Night's Death (also billed as The Chill Factor) is a 1973 made for television movie in the United States. The film was shown on January 30, 1973, on the ABC network. The film was directed by Jerrold Freedman and starred Robert Culp, Eli Wallach, and Michael C. Gwynne. Culp and Wallach are two research scientists at the Tower Mountain Research Station (based on the University of California's White Mountain Research Station) who are trying to unravel the mysterious death of a colleague.

Shock Of The New

Wiki:

Stendhal syndrome, Stendhal's syndrome, hyperkulturemia, or Florence syndrome is a psychosomatic illness that causes rapid heartbeat, dizziness, fainting, confusion and even hallucinations when an individual is exposed to art, usually when the art is particularly beautiful or a large amount of art is in a single place. The term can also be used to describe a similar reaction to a surfeit of choice in other circumstances, e.g. when confronted with immense beauty in the natural world.

The illness is named after the famous 19th century French author Stendhal (pseudonym of Henri-Marie Beyle), who described his experience with the phenomenon during his 1817 visit to Florence, Italy in his book Naples and Florence: A Journey from Milan to Reggio.

Although there are many descriptions of people becoming dizzy and fainting while taking in Florentine art, especially at the Uffizi, dating from the early 19th century on, the syndrome was only named in 1979, when it was described by Italian psychiatrist Graziella Magherini, who observed and described more than 100 similar cases among tourists and visitors in Florence.

Friday, January 7, 2011

Thursday, January 6, 2011

Whack A -

Wiki:

Villain hitting, Da Xiaoren (打小人) or demon exorcising is a folk sorcery popular in the Guangdong area of China and Hong Kong. Its purpose is to curse one's enemies using magic. Villain hitting is often considered a humble career, and the ceremony is often performed by older ladies.

The concept of "villain" is divided into two types: specific villain and general villain.

Specific villains are individuals cursed by the villain hitter due to the hatred of their enemies who employ the hitter. A villain could be a famous person hated by the public such as a politician or could be personally known to their enemy, such as when the request is to curse a love rival.

Villain hitters may help their clients curse a general villain: a group of people potentially harmful to the clients.

Dualism is mainstream in the traditional Chinese world view, and many different kinds of folk sorcery beliefs derive from this view. The concept of Villain (小人) and Gui Ren (貴人, people who will do something good to the clients) comes as a result of this yin and yang world view.

Receiving orders from clients, villain hitters require human-shaped papers with or without some information of specific people. As part of the ceremony, they beat the papers with shoes or other implements. The whole ceremony of villain hitting is divided into 8 parts:

- Sacrifice to divinities (奉神):Worship deities by Incense and Candle.

- Report (稟告):Write down the name and the date of birth of the client on the Fulu (符籙). If the client request to hit a specific villain, then write down or put the name, date of birth, photo or clothings of the specific villain on the villain paper.

- Villain hitting (打小人):Make use of a varieties of symbolic object such as the shoe of clients or the villain hitter or other religious symbolic weapon like incense sticks to hit or hurt the villain paper. Villain paper can also replaced by other derivative such as man paper, woman paper, five ghost paper etc.

- Sacrifice to Bái Hǔ (祭白虎):The hitter have to make sacrifice to Bái Hǔ if they want to hit villain on Jingzhe. Use a yellow paper tiger to represent Bái Hǔ, there are black stripes on the paper tiger and a pair of shape tooth in its mouth. During the sacrifice a small piece of pork is soaked by blood of pig and then put inside the mouth of the paper tiger (to feed Bái Hǔ). Bái Hǔ won't hurt others after being full. Sometimes they will also smear a greasy pork on Bái Hǔ's mouth to make its mouth full of oil and unable to open its mouth to hurt people. In some regional sacrifice the villain would burn the paper tiger or cut off its head after making sacrifice to it.

- Reconciliation (化解)

- Pray for blessings (祈福):Use a red Gui Ren paper to pray for blessings and help from Gui Ren.

- Treasure Burning (進寶):Burn the paper-made-treasure to worship the spirits。

- Zhi Jiao (擲筊) (or so-called "cup hitting" [打杯]):Zhi Jiao, to cast two crescent-shaped wooden piece to under go the Zhi Jiao ceremony

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)